Over the summer, we published a forecast for the 2012 presidential election based solely on election-year fundamentals. On the evening before Election Day, I am republishing the forecast. The only changes since summer come in the form of updated economic variables and approval numbers.

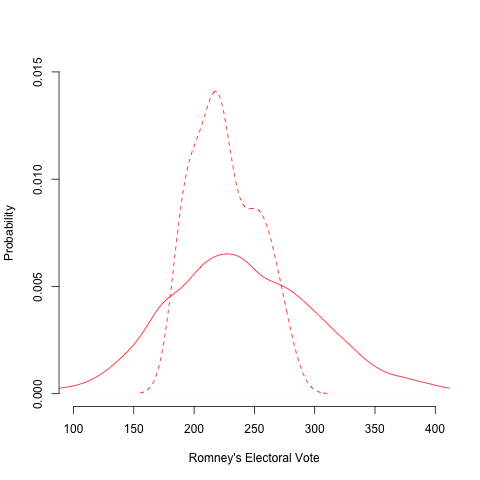

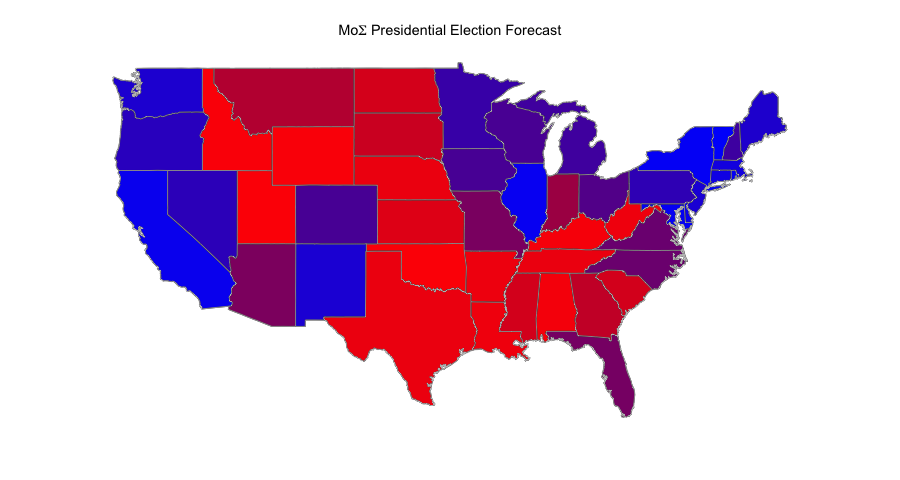

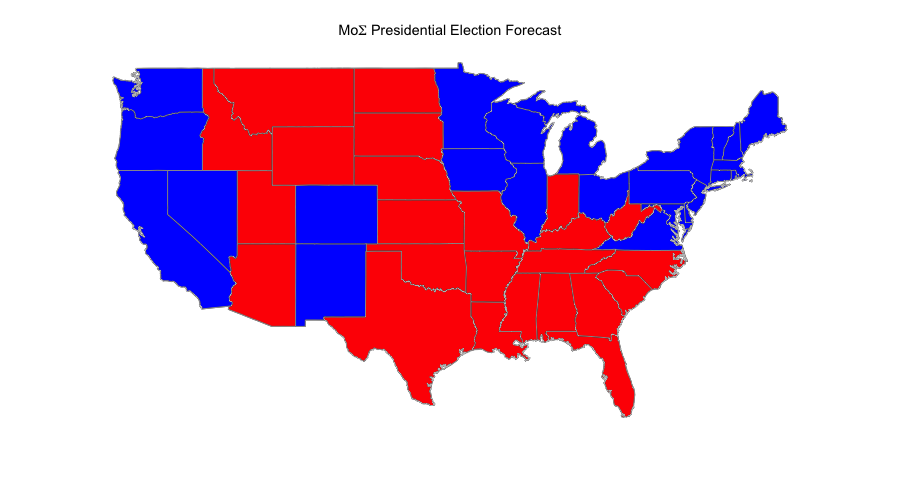

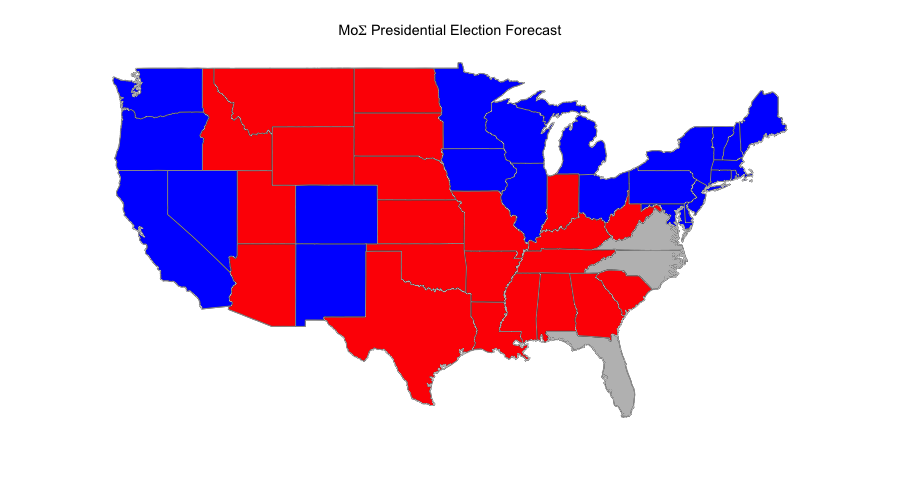

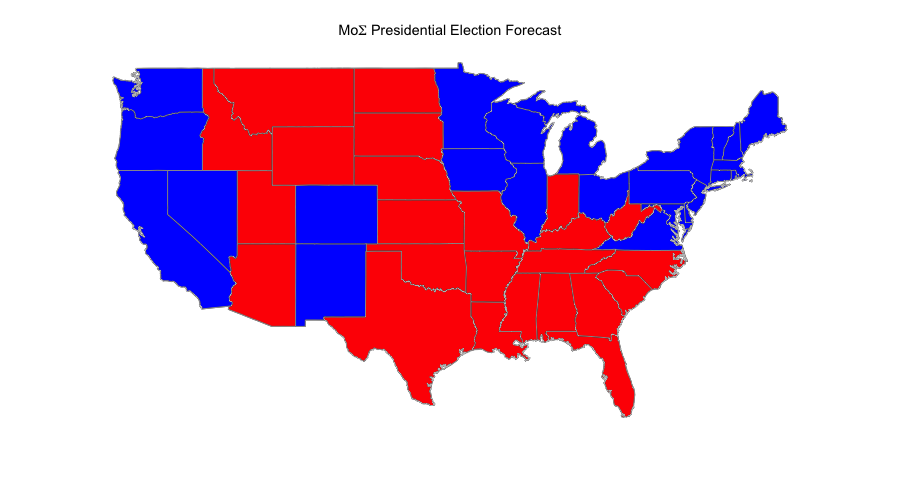

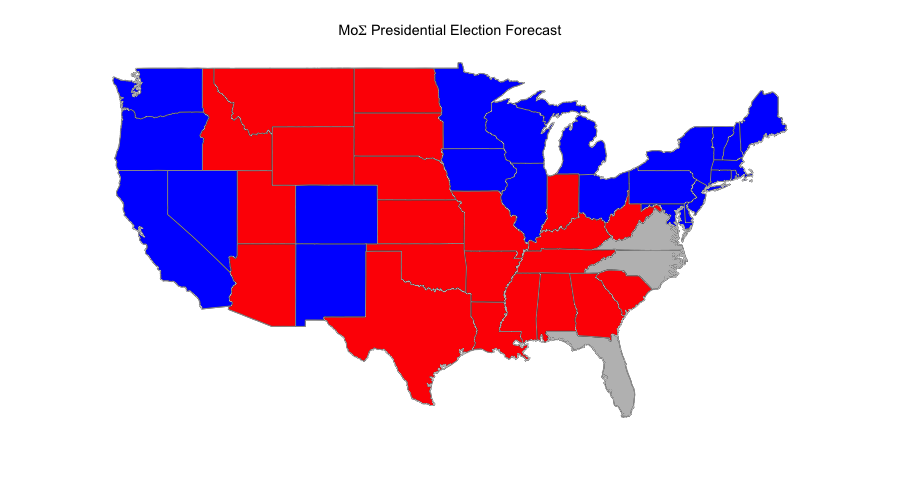

The model predicts Mr. Obama to win 51.5 percent of the national two-party vote to Mr. Romney’s 48.5 percent. Propagating these predictions to state-level results, the model forecasts Mr. Obama to secure 303 electoral votes to Mr. Romney’s 235.

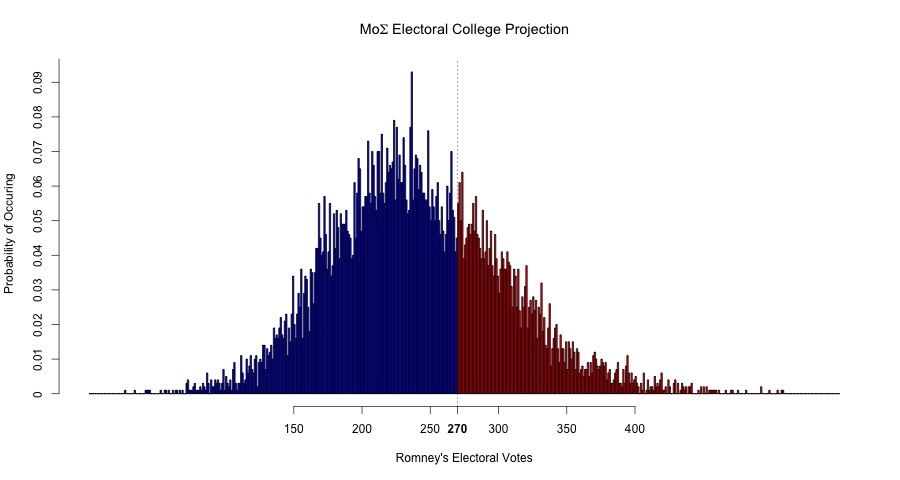

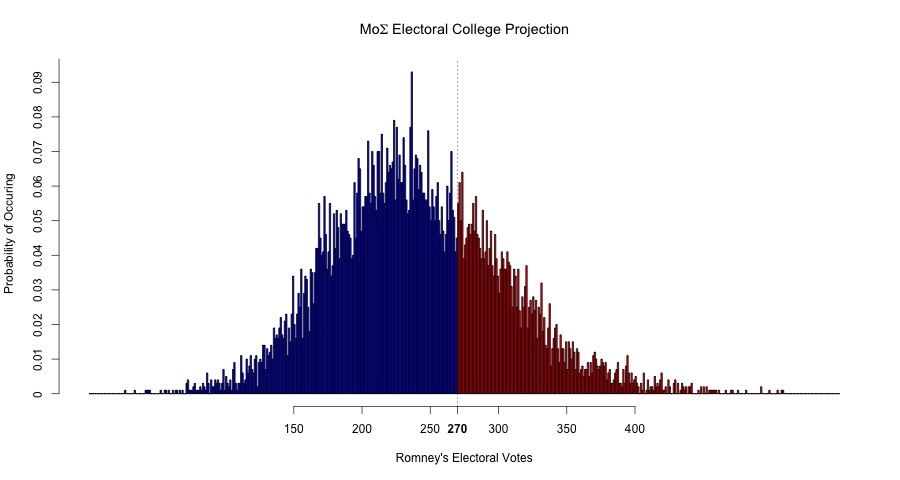

Over 10,000 simulations, Mr. Obama wins the election 68 percent of the time.

The model rests pretty comfortably in line with other social scientific models.

As I will expand on in a later post, one of the notable elements of the model is that it does not account for horserace polls. Unlike the models that get the most attention, this one only incorporates economic fundamentals for state-level predictions.

Accordingly, the model likely understates Mr. Obama’s advantage in Ohio, where the auto bailout seems to have made a dent in Mr. Romney’s chances. Working in the opposite direction, the model seems to overestimate Mr. Obama’s chances of winning Colorado, which most forecasts predict to be exceptionally close while the model gives Mr. Obama 53 percent of the two-party vote. For Colorado in particular, the model seems to be overly reliant on Mr. Obama’s favorable result there in 2008 and the state’s decent unemployment trajectory.

On the flip side, the model does not suffer from what’s undoubtedly haunting many Democrats: the chances that polls, with low response rates and undersampled cell-only households, are systematically incorrect. Put simply: without polling data included, the model doesn’t require polls to be accurate.

The model still comes with considerable uncertainty. In fact, the model may be overly cautious. Nate Silver’s model, for example, gives Mr. Obama a roughly 20-percent higher probability of winning than ours. That stems from multiple levels of uncertainty that we’ve added to the model: at the national, regional, subregional and state levels.

Though we can coerce the model into predicting a binary outcome in each state, we must note that several states are really too close to make a meaningful prediction. In particular, Virginia, North Carolina and Florida are forecast to come within a razor-thin margin of 1 point or less. Those states are, according to this naïve model, way too close to call.

All told, the model holds pretty closely to what we are seeing from other prominent models. Mr. Obama holds a definitive lead going into Election Day. Indeed, even were all too-close-to-call states to fall into Mr. Romney’s column, Mr. Obama would still secure reelection.