In Part I, we discussed popular media coverage of a forthcoming Psychological Science article. The work by Michael Bang Petersen and his colleagues claims to show an evolutionary link between physical strength and the intensity of political beliefs. In Part II, we’ll push that causal claim a bit further.

In the past few days, furor over the NSA surveillance program sparks new debates between liberals and conservatives. Interestingly, much the defense-versus-liberty arguments pit conservatives against one another: defense-hawks who want liberal power to root out terrorists, and libertarian-minded conservatives who abhor anything smelling like a police state.

This calls to mind the more traditional “liberals are like mothers, conservatives are like fathers” trope. Conservatives are tough and strong while liberals are warm and nurturing. The recent piece by Petersen and his colleagues plays, in part, into that stereotype. But how reliable is the research?

Revisiting Causation

Petersen and his colleagues find a correlation between bicep size (their measure of fighting aptitude) and the congruence between individual economic conditions and political conservatism. Why might the relationship exist? The authors argue that this clearly points to evolutionary and thus genetic bases of political attitudes. That’s not impossible, but it’s hardly the only reasonable conclusion to draw.[1]

Before we dig too deeply into the research, it might serve to review the basics of causal inference. Causation, as the name implies, seeks to establish that some phenomenon causes another. On its surface, this is simple to do. I flip the light switch, the light comes on. Boom: cause produces effect. Sure, there are mechanisms that allow the switch to work, but for all intents and purposes I caused the lights to come on.

Unfortunately, causal inference is rarely so simple. The cleanest way to observe causation is through randomized experiments, where some subjects receive a treatment (some rooms get the light switch flipped) and others don’t (some rooms’ switches are left untouched). If the treatment group experiences different outcomes than the control group, we may have observed a robust causal process.

With observational data (i.e., data collected by observation and not by experimentation), testing causal theories gets stickier. We can observe correlations, but we often cannot determine if x caused y, if y caused x, or if both x and y were caused by some other unobserved phenomenon z.

In political terms, we might ask: Does my evaluation of the economy determine my partisanship? Does my partisanship determine my evaluation of the economy? Does my political ideology cause both? Or might they all three interact in a more complicated way? With observational data, it’s hard to tell.

We don’t just abandon causal inference here, though. We can still make causal claims, but we must (a) provide thorough theoretical explanations for how our posited cause produces a certain effect; and (b) exhaustively examine alternate explanations that might falsify our theory.[2] Petersen and his colleagues tentatively satisfy the first condition, but hardly attempt at the latter.

Examining the Research

Turning back to the research, we can note first that the effects proffered by the authors are quite small. This illuminates the difference between statistical and substantive significance, which is frequently overlooked. The effect may exist, but it’s so small as to be swamped by other other influences in real world.

The more important challenge, however, critiques the authors’ causal claims. The authors posit that survival likelihood in men should cause more self-interested behavior, but they rather lazily support their case. In fact, the authors don’t even get close to providing an exhaustive test of their causal story.

The authors instead show a correlation between the two phenomena. Yet other reasonable explanations abound. Bicep size, after all, is not purely innate, but depends in large part on resistance training and even body fat percentage. And the predispositions toward having large arms may reflect little about evolution or genetics.

Certain people are more likely to believe strongly in physical aptitude and healthfulness, and perhaps these people are also more likely to hold strong political views. Education, for instance, tends to predict both political sophistication and physical exercise, health and lower obesity. Political science research also shows that knowledge and interest in politics play an important role in our ability to match economic policies and political elites to our personal economic well-being.

Or maybe the story does involve assertiveness, which makes individuals more likely to care about politics, behave more self-interestedly and/or hit the gym more regularly. The mechanism here could be nature, but it could also be nurture. Guys who are raised to assert their opinions on any manner of subjects, politics included, may also be raised to be physically strong.

Or perhaps self-interest causes physical fitness. It could be that people who are more self-interested also tend to care about physical strength. From a survival perspective, that would make sense. In fact, none of these alternative explanations are wholly unreasonable, and any of these explanations could produce similar correlations as expounded in the study.

Of Science and Old Sayings

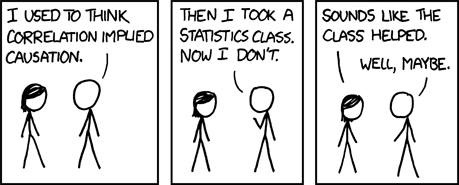

The age-old bromide “correlation does not imply causation” should be ringing in our ears about now. The authors have a mildly interesting finding, but at root all they’ve presented is a correlation which hardly supports their causal story.

Image courtesy of http://xkcd.com

Unless future research shows that other fitness characteristics, condition political attitudes, the theory remains weak.

Even in that case, researchers need to rule out competing theories. Strength might cause self-interest; but self-interest could cause strength, or both could be the effects some another evolutionary or behavioral cause.

What To Do?

How might researchers better examine the connection between strength and political attitudes? Let’s consider a few things to try.

1. Measure strength, not (just) biceps: The authors argue that biceps are the best single predictor of fighting ability. But why use just one? Surely there are reasonable ways to measure strength, like with compression springs, that would give us a better idea of how strong participants are. This eliminates concerns that bicep size might be a poor indicator of strength.

2. Measure fighting ability, not just strength: Biceps (or strength, otherwise defined) only matters to the degree that it taps into fighting ability. Other characteristics help us fight, though. Height and longer arms are useful, as are stronger legs and faster reflexes. The authors argue that biceps are used by others to assess a person’s fighting ability, but that should not matter for this study. The theory suggests that good fighters, not people who just look like good fighters, should take what they want from the political system.

3. Explore innate characteristics: Behavior, personality and interpersonal influence (parents, peers, et cetera) affect our tendency to lift heavy things. That makes it nearly impossible to say that strength per se influences our political views. More innate qualities, not as subject to behavioral manipulation, could be helpful.

4. Consider other dimensions of assertiveness: The authors argue that strong men will be more politically assertive; but why stop there? Asking, or experimenting, with other facets of assertiveness may shed light on an interesting question, namely whether strength predicts certain personality types, politics included.

In sum, it’s not surprising that conservative outlets latched onto the research without reading it thoroughly. Conservatives on my Facebook feed were certainly thrilled to learn that they were, in fact, ruggedly strong and athletic, standing in stark contrast to their pantywaist liberal counterparts. That’s motivated reasoning at it’s best, but its also wrong.

And frankly, I’m not even too surprised that a peer-reviewed article would oversell its findings. The research garnered a lot of attention and, if true, could constitute a generally interesting finding.

But science isn’t about pithy titles or provocative theories. Causal claims must be made carefully, especially when working with observational data without randomization and controlled treatments. Time will expose the authors’ theory to better tests, and I suspect that when that happens, the theory will find its way to the scientific dustbin.

Notes:

1. I’m fairly agnostic to using biological research in political science. Like all research subfields, it produces some good and some mediocre products. Some of the bio-politics research is actually interesting, some reflects a fetish for new data with little theoretical development, and some just mines for significance stars (see § 3).

2. This is actually a more optimistic view of causal inference in the social sciences than I tend to embrace. For an interesting read on causation writ large, I recommend Causality by Judea Pearl (see also here). For a grounded, if slightly depressing, view of statistical models and causal inference, David Freedman’s posthumous collection is a must read.

Pingback/Trackback

Seeing Red: A Statistics Debate