If you’ve struggled to find humor in politics recently, rejoice. At least the skewed-polls people are still around.

Yesterday, Chris Stirewalt blogged for Fox News that polls overstate support for gay marriage. Voicing a similar belief, leading social conservative Gary Bauer showed little concern over public opinion, telling Fox’s Chris Wallace:

“No, I’m not worried about it because the polls are skewed, Chris. Just this past November, four states, very liberal states, voted on this issue. And my side lost all four of those votes. But my side had 45, 46 percent of the vote in all four of those liberal states.”

As with many fallacies, there’s an iota of truth here. Stirewalt draws on work by New York University political scientist Patrick Egan that shows that late-season polls typically overestimate support for gay marriage compared with the election returns.

I don’t really have a problem so far. A Pollster article by Harry back in 2009 made a similar point and explored some ways to improve predictive models. The gap between pre-election polls and election returns, in other words, is well documented.

So, the polls are skewed…

Here’s where I depart from most interpretations of this observation. The poll-vote gap does not necessarily imply that the polls are “skewed.” Could it? Yes. But it doesn’t need to. I suspect a good bit of the bias comes from who votes not how they vote.

Stirewalt argues that the polls are skewed and mainly blames social desirability bias. In this line of reasoning, respondents do not want to admit opposition to gay rights for fear of social judgement; instead, they act supportive but cast their secret ballot against. In other words, the “true” level of support is systematically lower than the polls show.

What’s crazy to me is that Stirewalt, even after basing his entire argument on Egan’s research, ignores the part where Egan dismisses social desirability as the primary cause of the polls’ inaccuracy. And Egan couldn’t be much plainer about it: “On the whole, these analyses fail to pin the blame for the inaccuracy of polling on same‐sex marriage bans on social desirability bias” (p. 7)1.

What seems most likely is that pollsters haven’t figured out how to calibrate their samples to match the turnout. Ballot measures only attract at least moderately engaged observers. On an issue like gay marriage, it’s not surprising that some who ostensibly support gay rights aren’t nearly as motivated as those who have social, cultural or religious objections to it. The polls may decently represent the “true” proportion of citizens who support gay marriage, but not the class of voters who cast a ballot on the issue.

We’re Missing the Point

But far, far more importantly, any potential skew in the polls misses the true point here. Let’s assume that the polls are skewed, and that “true” support for gay marriage is actually seven points (best guess from the Egan research) lower than the polls say.

So what?

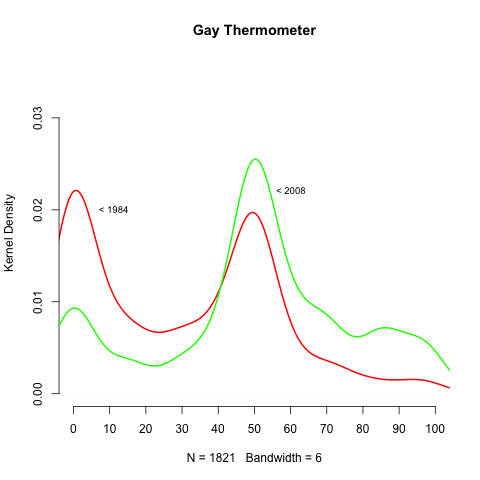

Those who invoke public opinion aren’t really that worried about crossing 50 percent. Even if the polls exaggerate support for gay marriage, the trend favors the equal rights argument. The above figure2 shows general sentiment (“thermometer” scores) toward gays and lesbians in the American National Election Study3. This figure by Nate Silver shows a similar rise in support for gay marriage. And this figure from Gallup shows a widening gap favoring general rights for gays and lesbians.

In this light, even yelling “Skewed Polling!” doesn’t change the fact that support for gays and their ability to marry is rising steadily.

Now I know that race and sexual orientation are not the same, but there are some similarities between the above kernel density plot and the one at the top of the post. In general, support for rights and general sentiment co-evolve. Sentiment toward black Americans has increased even in the post-Civil Rights era. We see a smaller but similar “swell” in sentiment for homosexuals, with every reason to think it will continue on its current trajectory.

Even if support today is really say, 51 percent instead of 58 percent, it’s much higher than it used to be.

Could we just be getting more politically correct, instead of more ‘liberal’, on gay rights? Sure, but the green line in the time series doesn’t show any real change in the rate of respondents opting out. No, young people are coming of age with a more permissive view on this issue.

Skew or no, the trend speaks for itself.

Notes:

[1] Now, as a brief aside, Egan’s first test for social desirability bias makes no sense to me. I can imagine plenty of reasons why a state’s gay population wouldn’t predict the poll-election gap. But the second test is much stronger: despite the social acceptance of LGBTs growing, the gap has become smaller. All in all, I’m sure social desirability is part of the story, but it’s most likely not the primary factor.

[2] The figure shows thermometers scaled on the interval [0, 1], as well as the proportion of respondents who respond to gays warmly (therm > 0.5), cooly (therm < 0.5), and those who opt to not answer. Confidence bands are generated using 1,000 bootstraps from the survey margin of error. The margin around “skip” seems odd, but for convenience I’m treating “skip” as an expression of a desire to not answer, and thus as a random variable in its own right.

[3] The ANES, funded by the National Science Foundation, could be at risk thanks to recent Congressional targeting of political science. Contact your representatives in Congress because (I promise!) most scholars use the study for more consequential research than I.

Lauren says:

This was awesome. Thanks!